Winner of the William P. Hanf Competition for Undergraduate Students

What is the William P. Hanf Competition?

A competition offered to my Calculus 1 class that I took with Professor Guerzhoy, in honor of a fondly remembered UH professor: William P. Hanf.

Link to website with more information: Professor Guerzhoy’s Website

Rules for the competition: Competition Rules

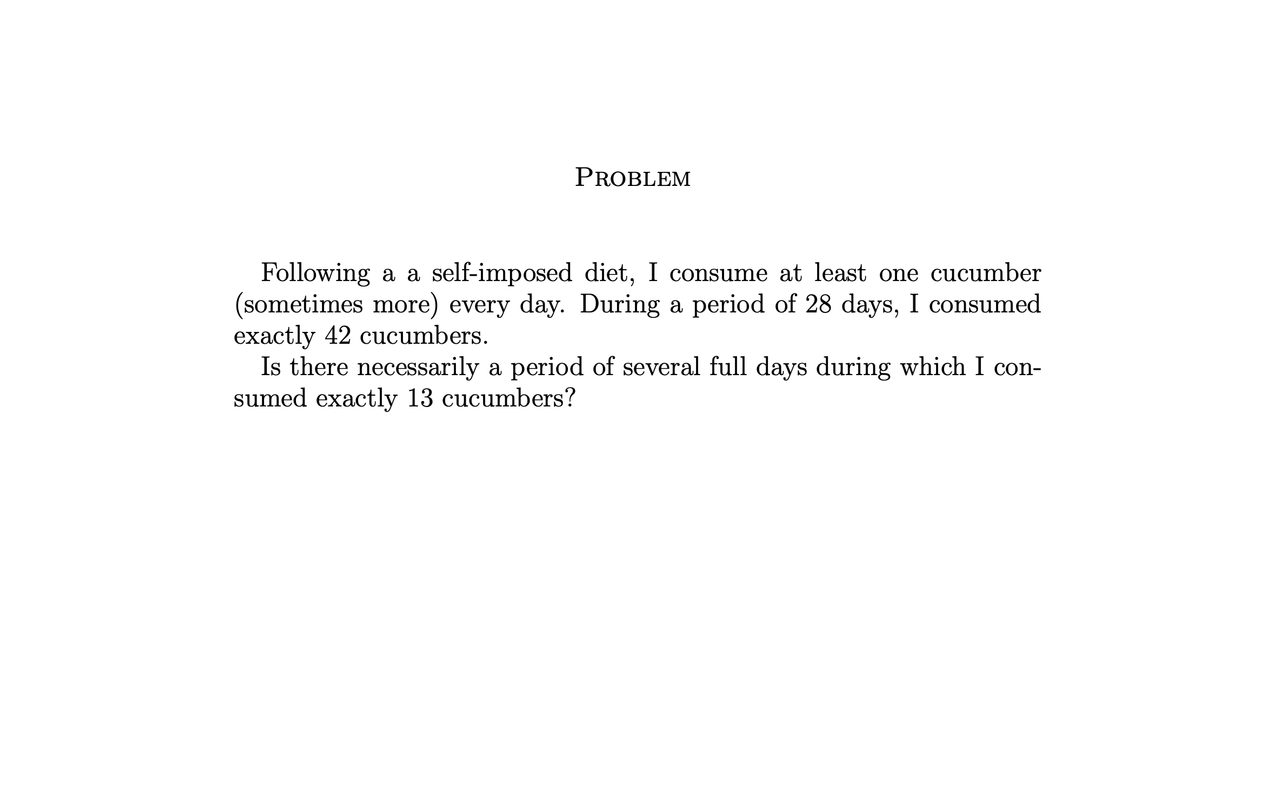

The Problem:

I was given a list of 13 problems to choose from, and I chose this one as it sounded more like a puzzle than a standard math problem. The primary application of the problem has everything to do with the Pigeonhole-Principle: an interesting mathmatical principle which has gone to prove things such as determining that there’s at least 2 people in London that have the exact same number of hairs on their head, to simpler things such as having a room filled with 367 random people guarentees that at least 2 attendees share the same birthday. Completing one of the problems was an extra credit opportunity which I never allow myself to let go. Thus began my journey into solving it.

Wikipedia link: Pigeonhole Principle

Completing the Problem:

Completing the problem took creating blocks of time each week where I could dedicate to solving it throughout the semester without impacting my other studies. Ultimatley, I was able to find the solution to the problem in the very last week of class! It turns out, there are many applications of the Pigeonhole Principle, but even just finding the right one was not enough to say the problem was a perfect one-to-one scenario to solving it.

I first began trying to solve the problem by physically writing out all the different permutaions of days to cucumbers which could be eaten. However, after an hour or two of writing, it was found out that attempting to note down all the number of permutations to prove whether there was neccessarily a period of several full days which the professor consumed exactly 13 cucumbers is near impossible. There needed to be another way.

Enter the Pigeonhole Principle. I found out about this principle about 1/3 of the way into the semester. It states that if n items are put into m containers, with n > m, then at least one container must contain more than one item. In the problem there are more cucumbers (pigeons) being consumed than the given days (holes), hence the connection.

The Solution:

This is part of the email that I sent to my professor on Dec 12th, 2023. It was later confirmed to be the correct solution the same day. Funnily enough, I had to make sure to check in with the professor in-person to make sure that if I had sent the correct proof on the final day, which it was, I’d still recieve extra credit. He allowed it and I found the solution just in time.

Aloha Professor,

I hope this email finds you well. Here’s my second shot at the problem.

Yes, there necessarily was a period of several full days during which you consumed exactly 13 cucumbers. This can be proven using the Pigeonhole Principle. The “pigeonholes” are the possible values ranging from 14 to 55, and the “pigeons” are the 56 values we obtain from the cumulative cucumber counts.

Let Xi represent the cumulative number of cucumbers eaten up to day i.

So, i = 1, … , 28 with a range of 1 ≤ X1 < X2 < X3 < … < X28 = 42

The objective is to find indices i and j such that Xi + 13 = Xj, indicating the consumption of exactly 13 cucumbers consecutively.

Considering the range of days, the values X1 + 13, X2 + 13, … , X28 + 13 = Xj range from 14 to 55.

14 ≤ X1 + 13 < X2 + 13 < … < X28 +13 = 55

We have X1 , X2 , … , X28 , X1 + 13, X2 + 13, … , X28 + 13

56 numbers that can be 55 different values.

For the Pigeonhole Principle, there are 56 numbers but only 55 possible different values, so we can conclude that at least one value must be repeated.

These values represent the cumulative cucumber counts on different days. Therefore, the repetition implies the existence of an i such that Xi + 13 = Xj, indicating a period of consecutive days during which exactly 13 cucumbers were consumed.

Xi + 13 = Xj

Credits:

Credits to where credit is due, I could not have possibly solved this problem without the help of my esteemed TA Alan Tong. He helped me to find the particular version of the pigeonhole-principle to utilize and refine the proof. I’m very grateful.

Source: Hall of Fame